Text last updated 1 November 2024

Contributed by: Brian L. Sullivan, Bryce W. Robinson, Nicole Richardson, Neil Paprocki, and Lizzy Chouinard

Introduction

The “Alaska” Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis alascensis) is an enigmatic taxon. Breeding in the temperate rainforests of coastal southeast Alaska and extreme western Canada, including offshore islands (e.g., Haida Gwaii), it is poorly represented in historical museum collections as well as in modern digital collections (e.g., eBird/Macaulay Library). It appears to be rarely encountered without concerted effort, especially during the breeding season. For example, Heinl and Piston (2009) report just a single example of confirmed breeding evidence for this taxon in the area around Ketchikan, Alaska, which should represent the veritable heart of its described breeding range. In this paper we review the original description and historical literature on alascensis, and provide clarification and additional commentary on the historical treatment of this taxon. We review the identification features, range, and movements of this taxon both in a historical context as well as in the modern context, with new information gained through review of digital specimens housed in the Macaulay Library.

Taxonomic Background

Buteo [borealis] alascensis Grinnell 1909

Type Specimens. Adult male, MVZ:Bird:51, Glacier Bay, Alaska, 19 July 1907, collected by Frank Stephens (https://arctos.database.museum/guid/MVZ:Bird:51) (Figs 1a; 1b); juvenile female, MVZ:Bird:41, Port Frederick, Chichagof Island, Alaska, 28 July 1907, collected by Joseph Dixon (Figs 2a, 2b). Grinnell (1909) described the taxon based on the above two individuals, designated as the type specimens, as well as two more adults collected during the same expedition (MVZ:Bird:42, MVZ:Bird:43) (Figs 3a, 3b; 4a, 4b). The latter two adults (42, 43) are presumably the parents of 41, since four birds (2 adults and 2 fully grown young) were encountered by Dixon and three were collected at the same time (Grinnell 1909).

Identification

Averages smaller than mainland North American subspecies; largest females have shorter wing chords than adjacent mainland males (Grinnell 1909, Taverner 1936, Clark 2018; see measurements in Preston and Beane 2009); all have darker dorsal plumage than calurus, borealis, and abieticola, some approaching harlani in this character. Adult. Most distinctive phenotype (e.g., Figs 3a, 5, 6) has variable rufous-washed breast contrasting with dark belly band, and creamy often unmarked lower belly and vent. Belly band variable but most frequently has scattered blackish longitudinal blobs over barring and a rufous-washed ground color; can be very light or nearly solid black. Throat ranges from dark to strongly contrasting white (a character, when present, that does not appear to be shared with calurus); when dark the throat is sometimes bordered laterally in white. Legs usually barred rusty to occasionally unmarked. Tail typically has a broad black subterminal band, variably banded black but can also lack interior banding. A whiter-breasted, white-throated variant occurs in the described breeding range and corresponds more closely with Grinnell’s (1909) adult type specimen (Fig 1a), but see Discussion below. Rufous-morph calurus is more uniformly rufous below, usually lacking the rufous breast versus paler belly/vent contrast shown by alascensis, and typically has a dark throat. Juvenile. Darker dorsally than calurus, and usually more heavily marked ventrally, with belly band ranging from nearly solid black to heavily marked with dense diamond-shaped or blobby markings; the lower belly, vent, and legs are heavily barred dark; dark tail bands average wider than calurus (Grinnell 1909, Clark 2018).

Polymorphism

Most authors consider the taxon monomorphic (Wheeler 2003, 2018), or express uncertainty as to whether it is polymorphic (Grinnell 1909), however, Pyle (2008) describes a dark morph as “blackish with brownish tinge” but gives no further detail nor mention of reference material or how he might have identified those birds as dark morph alascensis and not dark morphs of calurus or abieticola. True polymorphism status remains unclear, but based on a review of eBird/Macaulay Library images, it is certain that white-breasted, rufous-breasted, and dark-morph birds occur in the breeding season (here defined as 1 May – 15 August) within the described breeding range (eBird 2024; see Glacier Bay pair in Supplemental Data section). Whether these individuals are variants of “pure” alascensis or indicative of genetic mixing with adjacent calurus/abieticola/harlani populations is yet to be determined. It seems likely that whatever factors influence the large degree of polymorphism present in all three taxa that surround the range of alascensis (calurus, harlani, and potentially abieticola), would likely also be at play in shaping the evolution of polymorphism in alascensis. Note: Grinnell (1909) considered the specimens he examined to be light morphs, and noted uncertainty about the existence of a dark morph in alascensis. He went out of his way to note that these were not erythristic or melanistic examples—compared with rufous/dark morph calurus. Preston and Beane (2009, 2020) claim that Taverner (1936) identified alascensis as polymorphic, but upon review there is no such statement in that publication. Taverner (1936) recognized it as consistently smaller than calurus, but not identifiably different based on plumage.

Range

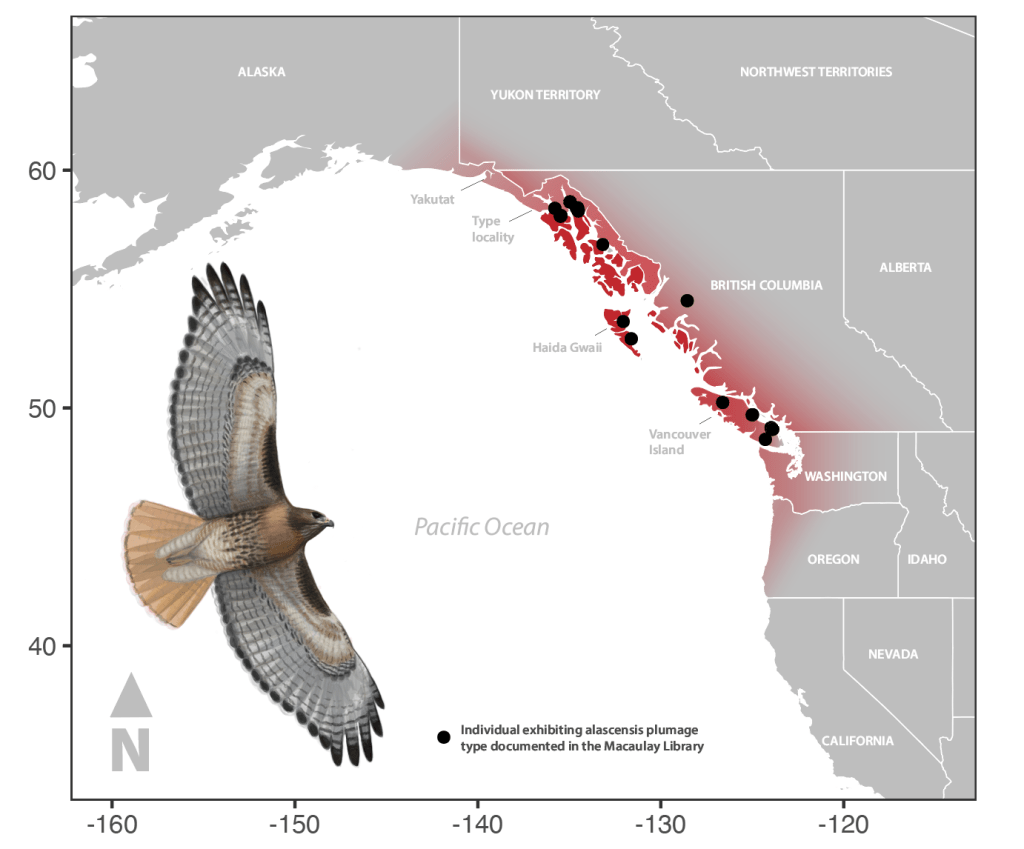

Breeds Yakutat Bay, AK, south through Haida Gwaii, BC, and on the immediate coast west of the Coast Mountains (Grinnell 1909, Gabrielson and Lincoln 1959, Wheeler 2003, Wheeler 2018) (Figs 5, 6). Grinnell (1909) and many subsequent texts include Vancouver Island as part of the breeding range (e.g., AOU 1957), but Wheeler (2018) noted birds there showing intermediate characters, likely representing an interface with calurus. Wheeler (2003) states that “Classic-looking individuals (i.e., rufous-breasted types) inhabit the isolated Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii)”, and Wheeler (2018) refers to the Haida Gwaii population as “possessing consistent plumage traits of this subspecies.” He also recognized variation within birds from across the breeding range, assuming it to be the influence of mixing with mainland taxa. He states that “the most unique-to-subspecies examples inhabit larger islands of this region, especially Haida Gwaii, BC.” We found a few typical alascensis birds on Vancouver Island during the breeding season (e.g., https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/347898531; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/478870291), but many more seem intermediate, and some seem like typical calurus (Figs 7-9; eBird 2024; see more Supplemental Data below). Winters sparsely in breeding range, with many birds moving south in fall essentially vacating the Alaska portion of the breeding range (Heinl and Piston 2009), but extent of southern nonbreeding range remains unclear. Birds on Haida Gwaii and Vancouver Island, as well as adjacent mainly populations could be resident (e.g., https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/526716341; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/612727669; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/529674611). Birds showing the distinctive adult phenotype mentioned above have been documented during migration as far south as Monterey, California (B. Sullivan; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/120070281). Further observation and documentation by keen observers, as well as novel tracking data, could help elucidate the southern extent of this taxon’s winter range in coming years.

Movements

Poorly understood and more study needed. For many years thought to be resident (Gabrielson and Lincoln 1959, Palmer 1988), but Wheeler (2018) suggests birds move south an ‘undetermined distance’ in fall, and provides a range map, though the southern extent appears to be arbitrarily cut off in northern Washington. Heinl and Piston (2009) report migration of this taxon in the Ketchikan area mainly between late March and early May, with peak counts occurring in April, and again from mid-August to November, with a fall peak in September. Anecdotal observations suggest that alascensis-type birds increase in Washington in the nonbreeding season (N. Paprocki pers obs), and this individual showing many alascensis characters was banded in October in north-central Washington (https://ebird.org/checklist/S95816404). A review of eBird/ML images seems to bear this out, with birds showing alascensis characters documented in winter in Washington (e.g., https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/90841761; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/287064351; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/208633161 ; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/291929811 ; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/45729031; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/85569511; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/440110641). To our knowledge no definitively identified individual of this taxon has yet carried a transmitter, but see Supplemental Data (below) for birds that show some alascensis characters that are carrying transmitters.

Status

Uncommon. Grinnell (1909) described it as “nowhere remarkable for its abundance”, and more recently Wheeler (2018) described it as “sparsely distributed and uncommon in near-coastal mainland areas west of Coast Mtns of BC and se AK”, with presumably the same density on the larger islands.

Discussion

An enigmatic taxon with relatively poor representation in museum collections as well as in eBird and the Macaulay Library. Similar birds occur on the mainland and well into the range of calurus, thus separation based on phenotype alone is difficult to impossible at this time, and more study is needed. We consider adults with strongly rufous-washed breasts in the described breeding range within the breeding season to represent this taxon, but whether the white-breasted types or dark morphs that occur there at the same time represent variants of alascensis or intrusions of other taxa into the breeding range of alascensis remains to be seen.

Grinnell (1909) described this taxon based largely on its smaller size and darker upperparts than other Red-tailed Hawk taxa, but he did not mention the most distinctive character that has subsequently been used to identify adults: the strongly rufous washed breast. This strong wash is only present on one of the three adults specimens Grinnell examined for the original description (Fig 3), and only weakly present on one other (Fig 4). Grinnell’s comment “the relatively unmarked chest region is suffused with a strong tinge of cinnamon” pertained to his description of the fresh juvenile type specimen (juvenile female, MVZ 41, Port Frederick, Chichagof Island, Alaska, 28 July 1907), not the adult male type specimen or the other two adults on which he based his original description. Note: Gabrielson and Lincoln (1959) later compressed Grinnell’s 1909 original description of the adult and juvenile plumages of alascensis into a single alascensis ‘Description’, leaving out Grinnell’s important age-related details and conflating the characters Grinnell described for the juvenile as pertaining to all alascensis. Clark (2018) reported this strong rufous wash on 25 of 27 adult specimens, although no information on specimen numbers, dates, or locations was given. Nonetheless, this character appears to be strongly indicative of this taxon in this part of the species’ range. It is not, however, limited to birds that occupy alascensis’s described breeding range, as this rufous-breasted influence can be seen on birds in the breeding season around Vancouver (e.g., https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/339335521) as well as much farther east and south in British Columbia and Washington (e.g., https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/231307461; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/112583271; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/478341351; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/604742191; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/476963411; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/364689421; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/127330061). Away from these areas the rufous-breasted influence mostly disappears, but occasional individuals in the breeding season can show similar features far from the range of alascensis (e.g., https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/236686701; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/31145931; https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/249461461).

Whether alascensis is a valid subspecies or a morph of calurus requires further study. Taverner (1936) offered guarded acceptance of alascensis as a subspecies after first suggesting that it was not safely separable from calurus. Taverner (1936) examined 8 juveniles and 1 adult male. “As far as color goes there is nothing distinctive from calurus in any of these Queen Charlotte birds. However, all are consistently and distinctly small, the largest female (wing 368 mm.) being smaller than the smallest male in the transcontinental series, except some of the eastern borealis variants. They can be described as small calurus and as such upon present evidence can be given rather guarded acceptance as a subspecies of Buteo borealis.” Taverner (1927), however, did not feel the same way! “The points of distinction (e.g., smaller size, richer color), seem too fine and inconstant to be dignified with subspecies recognition.” He illustrates a typical adult and calls it calurus in that publication (Plate II; Figure 8. 14112. Adult female. Tow Hill, Graham Island, Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia, 7 August 1919). He describes it as “A dark, reddish calurus, typical of a type common in British Columbia, especially toward the coast, but which does not seem to be found on the prairies in breeding season”.

Wheeler (2003) described alascensis as ‘marginally separable from calurus’. He examined 5 adult breeding season specimens, and describes the breast as “overall somewhat mottled or nearly solid dark rufous”(yes!), and continues with, “Overall appearance of the underparts is a dark rufous breast with some pale mottling, moderately heavy or heavy blackish belly band, and paler lower part of the body.”–a good description of the general characters of the “classic” adult type.

Later, Wheeler (2018) recognized more confusion in the birds breeding within the described range of alascensis. He refers to the Haida Gwaii population as “possessing consistent plumage traits of this subspecies.”, and concluded that “separating this subspecies from some variations of “Western” can be difficult in the field.” Indeed, his next statement indicates just how vexing this challenge can be: “’Alaskan’ birds are sparsely distributed and uncommon in near-coastal mainland areas west of Coast Mtns of BC and se AK (S. Heinl, A Piston pers comm) where they undoubtedly mix in some locations with “Western”. The most unique-to-subspecies examples inhabit larger islands of this region, especially Haida Gwaii, BC. Some adults of se. AK, including outermost islands, such as Baranof, appear to align more with “Western” subspecies are perhaps intergrades with “Alaskan”. Some individuals from Haines, AK, have pale supercilium patches and white ventral areas and do not appear like this subspecies but likely have “Harlan’s” influence; other birds are identical to classic light morph “Western”. Birds from Juneau mainly appear as good examples of this subspecies.” Wheeler considers birds from Vancouver Island to be “Western” and not alascensis, but our review of images show birds with both typical alascensis characters and many with mixed characters in the breeding season on Vancouver Island, suggesting this is an area of mixing.

Conclusion

More study needed! A central tenet of the modern definition of subspecies requires that any valid described subspecies must inhabit a breeding range apart from that of any other subspecies. In the Red-tailed Hawk we rarely see subspecies safely satisfy this criterion, leading us to wonder whether that criterion is best applied to taxa that are not in such a state of flux, as the Red-tailed Hawk currently seems to be. Post-glaciation, many distinct forms likely came into contact with each other, yet the barriers to assortative mating were not significant enough to prevent rampant interbreeding, resulting in the great melting pot of Red-tailed Hawk taxa we see today, with phenotypic features still restricted to birds that breed within those old glacial rufugia, but with many intermediates and interlopers of other taxa now muddying the picture. Whether these can still be considered subspecies is a good question, but this situation applies to even the most distinctive taxa in the complex, including B. j. harlani and B. j. kriderii.

References

American Ornithologists’ Union. 1957. Check-list of North American Birds. Fifth Edition. American Ornithologists’ Union.

Clark, W.S. 2018. The Alaska Red-tailed Hawk. Western Birds 49: 126-135. DOI 10.21199/WB49.2.3

eBird. Accessed November 2024. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY.

Gabrielson, I.N., and F.C. Lincoln. 1959. The Birds of Alaska. The Stackpole Company, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and the Wildlife Management Institute, Washington, D.C.

Gibson, D. D., and Kessel, B. 1997. Inventory of the species and subspecies of Alaska birds. W. Birds 28:45–95.

Grinnell, J., Stephens, F., Dixon, J., and E. Heller. 1909. Birds and mammals of the 1907 Alexander Expedition to southeast Alaska. University of California Publications in Zoology. Volume 5, Number 2, 174-264.

Heinl, S. C., and Piston, A. W. 2009. Birds of the Ketchikan area, southeast Alaska. W. Birds 40:58–144.

Hellmayr, C. E., and Conover, B. 1949. Catalogue of birds of the Americas, part I, no. 4. Zool. Ser. Field Mus. Nat. Hist. 13 (publ. 634).

Palmer, R.S. 1988. Handbook of North American Birds. Volume 5. Family Accipitridae: Buteos. Yale University Press.

Preston, C.R., and R.D. Beane. 2009. Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.52

Preston, C.R., and R.D. Beane. 2020. Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.rethaw.01

Pyle, P. 2008. Identification Guide to North American Birds: Part II. Slate Creek Press, Point Reyes Station, California.

Swarth, H.S. 1926. Report on a collection of birds and mammals from the Atlin region, northern British Colombia. University of California Publications in Zoology, Volume 30(4): 51-162.

Taverner, P.A. 1927. A study of Buteo borealis, the Red-tailed Hawk, and its varieties in Canada. Victoria Memorial Museum, Museum Bulletin No. 48. Biological Series, No. 13.

Taverner, P.A. 1936. Taxonomic comments on Red-tailed Hawks. The Condor, 38(2): 66-71.

Wheeler, B.K. 2003. Raptors of Western North America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Wheeler, B.K. 2018. Birds of Prey of the West: A Field Guide. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Supplemental Data

Below we document four different Red-tailed Hawk phenotypes (classic alascensis, the white-breasted type, harlani, and an unknown dark morph subspecies) nesting less than five miles from each other!

Glacier Bay Nesting Pair 1, Gustavus, AK, 22 July 2018 (https://ebird.org/checklist/S47367698); all photos by Nat Drumheller.

The pair below was photographed very close to where Grinnell’s (1909) type specimens were taken. The light morph is not far away from his white-breasted male type specimen. The dark morph is of unknown subspecies, but could represent dark morph alascensis or an intruding dark morph calurus/abieticola individual. It doesn’t appear to show any harlani characters.

Glacier Bay Nesting Pair 2, Gustavus, AK, 26 June 2020 (https://ebird.org/checklist/S70864844); ; all photos by Nat Drumheller.

This pair includes a typical rufous-breasted alascensis type breeding with a typical light morph harlani.

Tracked Individuals

Hamlin–Strong rufous wash to breast, paler vent, dark dorsally. Banded and tagged in eastern Washington, then moved nearly straight west to breed (?) or over-summer south of McIntosh, WA.

https://ebird.org/checklist/S125542321

Snohomish–Strong rufous wash on breast with paler buff vent and very dark dorsally. Resident north of Snohomish, WA.

https://ebird.org/checklist/S130958619

2023 year-round distribution of Snohomish

Skagit–strongly washed rufous on breast with cleaner vent, dark dorsally with little pale mottling in scapulars. Resident near Skagit, WA.

https://ebird.org/checklist/S130935659