A few weeks ago, Bryce had the pleasure of presenting the project on the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Birds of the World Webinar. Take a look at how Bryce frames the work we are doing, and the updates he shares on what we’ve discovered so far!

A white Red-tailed Hawk from Oklahoma

Some incredible luck struck on a recent trip to Oklahoma (more on the trip soon!) that included some core project folks as well as a few keen Cornell University undergraduate students. While on the trail to trap harlani and intergrade types, Irby Lovette and undergrad Mei Rao came across a striking all white Red-tailed Hawk. After the rest of the group caught up, we had the incredible fortune to capture the individual.

One very interesting take away from this individual is the importance of pigment for feather durability and structure. In both of the wing out images above, the molt limits in the primaries are strikingly obvious, with the old feathers being extremely worn. Without melanin in these feathers, they degrade substantially.

Another interesting note is that at first glance the bird appears to be entirely white, but there are flecks of color in a few locations on the body. In particular the bird has a few dark, fairly normally pigmented feathers on the nape, and the rachis of the central tail feather is partly pigmented orange. There are many mutations that might cause this look to a bird and it is impossible to know exactly without a molecular analysis, but because of the normally pigmented iris, bill, and the bits of color in the few locations on the body, we do know it is not albinism. Our guess is that the bird might be an example of a plumage aberration that slowly turns the bird white across its life called ‘Progressive Graying’.

Also notable to us were the white talons, with bits of pigment in a few. It is curious that the irises have normal pigment, and the bill seems to as well, but the talons are affected. Without knowing for certain at the moment, one supposition is that the rate of growth in the talons might be much higher than the bill, or perhaps the localized effect of the aberration is just random and for no reason other than chance has not affected the bill.

Because the individual lacks any plumage features, it is next to impossible to assign it to a subspecies or to know at all where this bird might breed (morphometrics do help, but not entirely). After some deliberation, the group decided to place a tracking unit on the bird. We’ll be sure to post about its full cycle wanderings when we receive the data, but our guess is that the bird is actually a harlani and ends up somewhere in Alaska this summer. We shall see!

To see more of this bird, check out the eBird checklist: https://ebird.org/checklist/S163166668

All of these photos were taken by Nicole Richardson and are deposited in the Macaulay Library.

The Mississippi Miracle

One big component of the Red-tailed Hawk Project focuses on understanding movement ecology, including migratory, breeding and wintering ground movements. However, it is not feasible to put a transmitter on every bird we capture so in conjunction to our transmitter effort have put color bands on birds across their North American range. To effectively do this, individual researchers have a unique color combo to represent certain regions and the specific populations that move through those areas.

Nick, who bands migrants passing through the Straits of Mackinac in Michigan, uses white color bands that contain a black two digit alpha-numeric combo. Nick has been putting out color bands for two years now on breeding and non-breeding adults, and juveniles. One of our hopes with color banding juveniles is to see areas these non-breeders use throughout the year. We are also hoping to document the plumage progression in various subspecies as they molt from juvenile to adult plumage, something that remains a mystery because of the vast phenotypic variation among juveniles, especially among the subspecies abieticola.

Color banded 3Y in juvenile plumage (May 2023)

Color banded 3Y in adult plumage spotted in Jackson County, Mississippi

Now the exciting news. A juvenile abieticola that was banded in May of 2023 in the Straits region was recently resighted in Jackson County, Mississippi, near the Gulf of Mexico. This is also the furthest south we have had a Michigan migrant winter. With this we were able to document the change in plumage for what we would consider a more heavily marked juvenile of this subspecies.

Hopefully this has inspired you to look a little closer at the next Red-tail you see when you are out birding and to check and see if they too have a color band. If you do you can report the auxiliary marker (color band) here where you will be awarded a certificate for your effort and if you are lucky enough to get photos, please post those to Macaulay Library and ebird as these data are incredibly valuable.

The full set of photos for the resighted bird can be found here. I’d also like to thank Mike Borle for passing along this information about this resight from the Red-tailed Hawks of the United States Facebook page and of course Sharon Milligan for snapping some great shots of this bird!

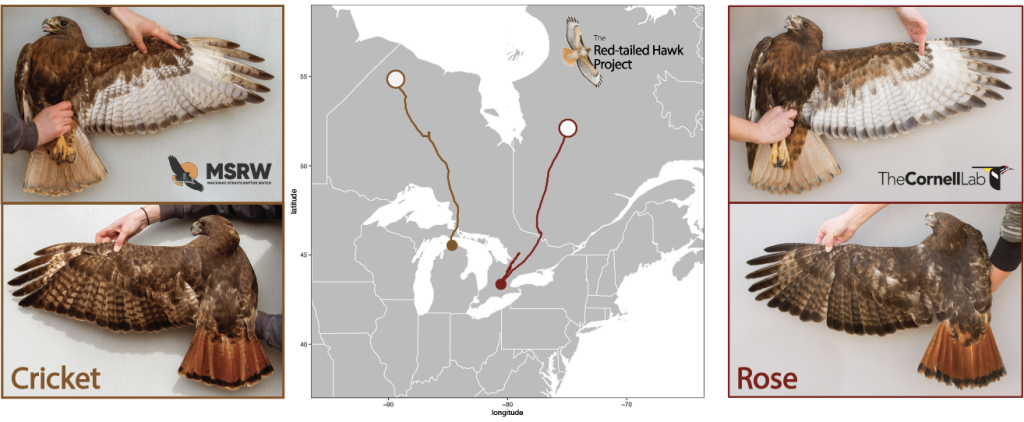

Dark morphs breed in the eastern boreal forests of Canada

We’re currently celebrating some success from last years transmitter effort. Two of the dark birds we tagged, one that Nicole and Bryce caught in Ontario and one that Nick caught in Michigan, have returned for the winter and provided us with an insight into where they spent the summer. Both individuals spent their summer almost directly north of where they were caught, one in the northwest of Ontario and the other in the northern parts of Quebec (white circles in the figure).

Given their movements throughout the summer, we have reason to believe that both of these birds bred at these sites. In a forthcoming publication, we’ll outline their full cycle movements as well as provide an in depth description of their movements from the breeding season to support their breeding activities.

Does abieticola have a dark morph? An oversimplified answer seems to be yes, but we need to do more work to fully support this. The only way to confirm this is to do genomic analyses that will strengthen our understanding of the true origin of these dark types, and why we see them in the east at such a low frequency. For instance, these individuals could represent broad dispersal events from the west, and their offspring could face strong selective pressures that limit the true establishment of dark phenotypes in the east. The presence of these breeding adults may be explained by dispersal events that occur at such a frequency every generation but not result in the establishment of dark individuals that are genetically part of abieticola, or this far northeastern population of Red-tailed Hawks.

Our ability to put together this perspective on the origin of dark morphs that winter in the east is only possible through collaboration. Birders and ornithologists have wanted to answer the question of where these dark birds in the east originate for a long time, and the only way we have been able to uncover this is by working together. Under the Red-tailed Hawk Project, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Mackinac Straits Raptor Watch, and Hawk Ridge Bird Observatory, with support from the community, have all come together to answer this question. Stay tuned for a publication in the coming year that provides more details on these birds, and the coming genomic work that will help us further understand plumage polymorphism in this wonderful species.

See the eBird checklists for both of these birds:

Rose – https://ebird.org/checklist/S129215816

Cricket – https://ebird.org/checklist/S132717127

Twelve new transmitters deployed in Grande Prairie, Alberta

Nicole and Bryce recently teamed up with a good friend of the project, Sylvain Bourdages, in Grande Prairie, Alberta for a week of exciting field work. An isolated patch of agricultural land surrounded by dense boreal forest, this area is a famous stopover for an incredible diversity and abundance of Red-tailed Hawks. At least, it is in a normal year! Sylvain has lived in the region two decades now, and has noticed that birds not only arrived later than usual, but were also relatively scarce overall this spring.

But in spite of the unusually quiet backroads, the week was a great success with twelve new transmitters deployed on an excellent suite of fascinating phenotypes. Now we eagerly wait to see where these birds will go to breed this summer!

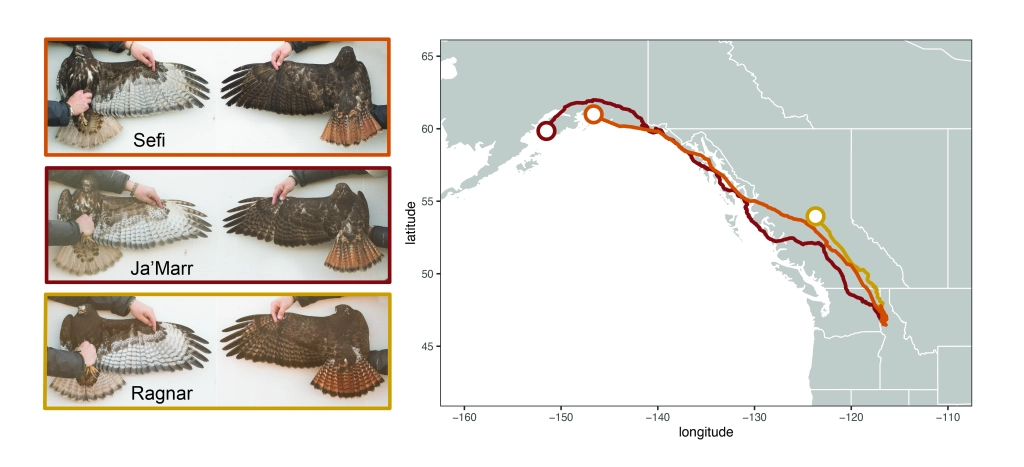

Comparing plumage, movement, and summer locations in three dark morphs

We are fortunate that three of our birds have settled in summer locations that are in range of a cellular tower, so we are receiving regular updates on their movements. Two of these individuals took an exciting spring migratory route that we haven’t seen until now. Sefi and Ja’Marr moved along the coast of British Columbia and southeast Alaska, hopping from island to island and passing over cities such as Juneau. Eventually, both birds ended up in south central Alaska. Comparing these two individuals against Ragnar, who ended up at a breeding site in central British Columbia, creates an opportunity to look at the similarities and differences in their plumage, age, and purported sex to provide some interesting context to the movement patterns we are seeing.

These individuals are similar in many aspects of their plumage. They are all dark morphs, with fully red tails. Ja’Marr and Sefi each have harlani like streaking in the breast, while Ragnar is a very deep dark and solid brown throughout the body. The other striking difference is in the tail pattern, where Ragnar has rather thick and regular tail banding while the other two birds have irregular barring that is mostly restricted to the base of the tail, and includes harlani-like spotting. Although Ja’Marr is not breeding (as indicated by it’s more irregular and widespread movement patterns), it is interesting to compare the plumage similarities between Ja’Marr and Sefi, and the proximity to their summer locations, to Ragnar’s breeding location. These individuals are an important contribution to understanding whether or not birds like Sefi and Ja’Marr that occur well within the distribution of harlani represent the phenotypic diversity of that population, or represent plumage traits that come from calurus to the south, and occur because of contact and interbreeding.

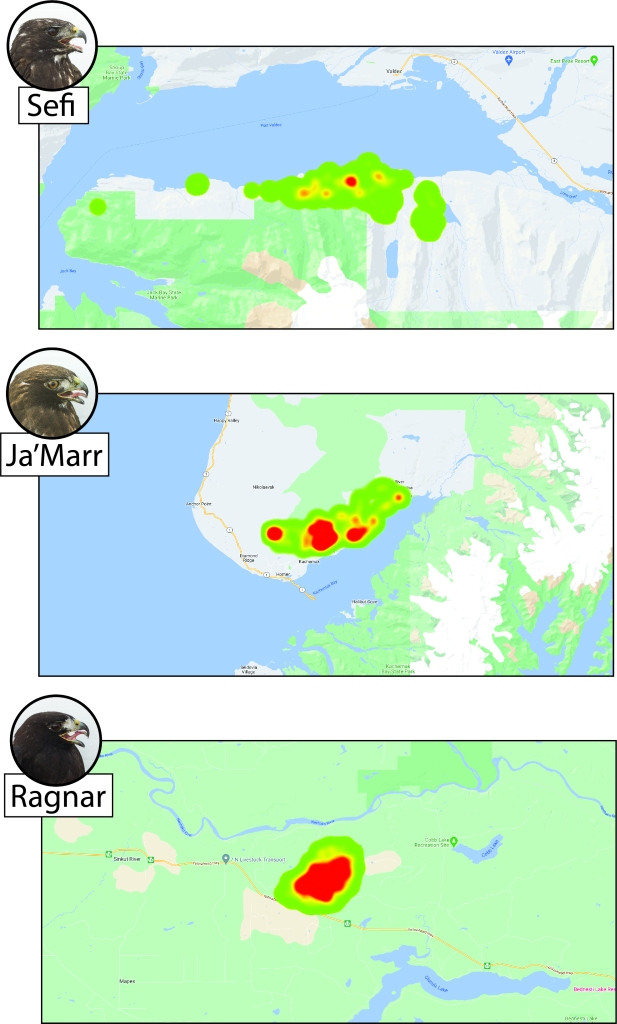

The image above illustrates the home range pattern in a heat map for each individual for the month of June. The red clusters indicate areas of high use. Sefi seems to have nested in a site across the bay from Valdez, however there is some spread to the points. Contrasted against Ragnar, who also seems to have bred, the difference is striking. Ragnar has a very centralized, almost circular cluster pattern suggesting that the bird is tied tightly to a nest location. The difference between these two nesting patterns could be explained by sex. Based on morphometrics at the time of capture, Ragnar was tentatively sexed as a male while Sefi was tentatively sexed as a female. At face value, the patterns in their movements don’t make much sense considering their likely sex, since the female is more tied to the nest during the first part of the nesting period, while the male is more random in his movements as he works to provision the incubating female, and later, the young brood.

Ja’Marr’s movements are widespread, with multiple areas of high use. The lack of a centralized home range pattern suggests that Ja’Marr did not breed this summer. This makes sense, since the bird was a second-cycle at the time of capture this past winter. Generally, Red-tailed Hawk do not breed until the end of their third or fourth-cycle. Ja’Marr represents what is termed as a ‘floater’, or an individual that has not yet joined the breeding population. These floaters drift around until they find an opportunity to breed. If all goes well, we may capture when this occurs for this individual. Taken together with other birds we tagged as second-cycles, we can provide some very interesting insight into patterns of movement during the floater period, as well as the timing of recruitment into the breeding population.

Although at the moment we can only mostly speculate about the patterns we are seeing, we are situated to confirm most of our suspicions. For instance, we can confirm the sex of each individual using molecular techniques, and take a more systematic approach to analyzing the data to investigate what factors (such as sex, age, etc) best explain the movement patterns we see. There is a lot of exciting things to dig into, so stay tuned for more.

A band recovery connecting eastern Kansas to Grand Prairie, Alberta

Last month, Bryce caught this stunning dark bird just north of Lawrence, Kansas and discovered that it was already banded. After reporting the band and asking around, he learned that the individual had been captured and banded near Grand Prairie, Alberta in May 2015 by Sylvain Bourdages, an active raptor bander and friend of the project. Even more, Sylvain happened to take photos of the bird that he willingly shared. This provides an excellent comparison between juvenile and adult plumage, as well as a known age for this bird. When it was banded in May 2015, it was still in its first cycle (Juvenal) plumage, despite that it had started its second prebasic molt. Thus, this bird can now be aged as an eighth cycle. From the molt limits in the primaries in the photos above, we can estimate its age as after fourth-cycle, a pattern that is not often seen and generally is assumed to suggest a rather advanced age bird. It is then a valued insight to see this pattern on a bird that we know is in its eighth cycle.

This bird that we now call Ben is outfitted with a GSM transmitter, and we will provide updates when we have a nesting location, and eventually its full cycle migratory path. Another benefit of this recapture event is to contrast the information we gain from the banding effort against the information we gain from the transmitter effort.

Thanks to Sylvain Bourdages for all of his efforts to capture and band migrants in his region of Canada, and for the wisdom to photograph every bird he gets in hand. Because of his efforts and those of folks like him, this will likely be the first of many of these types of recoveries for our research program.

A juvenile hybrid Red-tailed X Rough-legged Hawk captured in eastern Kansas

Luke and Bryce recently captured this amazing juvenile Rough-legged x Red-tailed Hawk hybrid in eastern Kansas.

Here is our breakdown of the identification – Note the multiple Rough-legged Hawk traits such as head coloration and pattern, including pale auriculars; subtle carpal patch; buffy base coloration to breast and underwing; pale and unpatterned base to flight feathers on wing, especially in the primaries; seemingly unpatterned greater upperwing coverts (expected to be more patterned in RTHA, especially harlani); fairly solid and noticeable bellyband that sits lower than expected for RTHA; long wing and tail measurements; relatively small feet for RTHA; and tarsi feathering more extensive than RTHA. Otherwise, the bird looks mostly like a juvenile harlani in plumage, especially the tail pattern.

Our hope is that over the next few years, we are able to capture other individuals like this to better understand the regularity of hybridization events in the Red-tailed Hawk. For now, eBird and the Macualay Library are serving as great resources for strengthening our understanding of how often this hybrid pair occurs. You can explore images of hybrid Red-tailed X Rough-legged Hawks in the Macaulay Library here.

An attempt to better understand the Krider’s Red-tailed Hawk (B. j. kriderii)

One of the research goals of the Red-tailed Hawk Project is to better understand the “Krider’s” Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis kriderii). There has long been debate about the validity of this currently recognized subspecies, because of its variability and that it breeds alongside (and with) birds we consider as the subspecies borealis. The two most popular competing thoughts are that 1) borealis expanded its distribution westward into the northern Great Plains along with the westward expansion of European settlement (consider homesteading and the resulting increase in trees) and is currently in a slow process of subsuming kriderii, or 2) kriderii represents a pale morph of borealis that is found in the northern Great Plains. The two may actually not be mutually exclusive, but for now our approach is to focus on collecting data so we can gain some insight that might inform a better perspective on the situation.

Bryce recently tagged 5 individuals in southern Louisiana, and 1 individual in western Missouri that all possess kriderii traits to some degree. The hope is that each will soon return to their breeding territories. Unlike the more northerly breeding phenotypes we have tagged, we should obtain breeding locations as the birds begin their reproductive effort this spring. Once we do, Bryce plans to travel to each territory and record the mate for each of these birds, and photograph the phenotypes of the offspring that come from each pair. Our hope is that this will compliment genomic analyses to describe the relatedness of individuals that posses kriderii traits, and those that are borealis in plumage.

Many thanks to the individuals in Louisiana that helped Bryce – Matt Mullenix, Garrett Rhyne, Dylan Bakner, and Patty Rodriguez.

“Liggy” the light morph harlani

Over the weekend, Neil Paprocki caught and outfitted this light morph harlani with a GPS/GSM transmitter in Northern Idaho.

The members of our group decided that this harlani, the first bird to be tagged for the winter 2021/2022 field season, is to be named “Liggy” in honor of our mentor and friend Jerry Liguori. “Liggy” will be our flagship bird as we work to understand the unique plumage characteristics of harlani, and how this outstanding subspecies relates to the rest of the Red-tailed Hawk populations across North America.