“Socorro” Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis socorroensis): a taxonomic review with an expanded understanding of phenotype

Contributed by: Brian L. Sullivan, Bryce W. Robinson, Nicole Richardson, and Lizzy Chouinard

Introduction

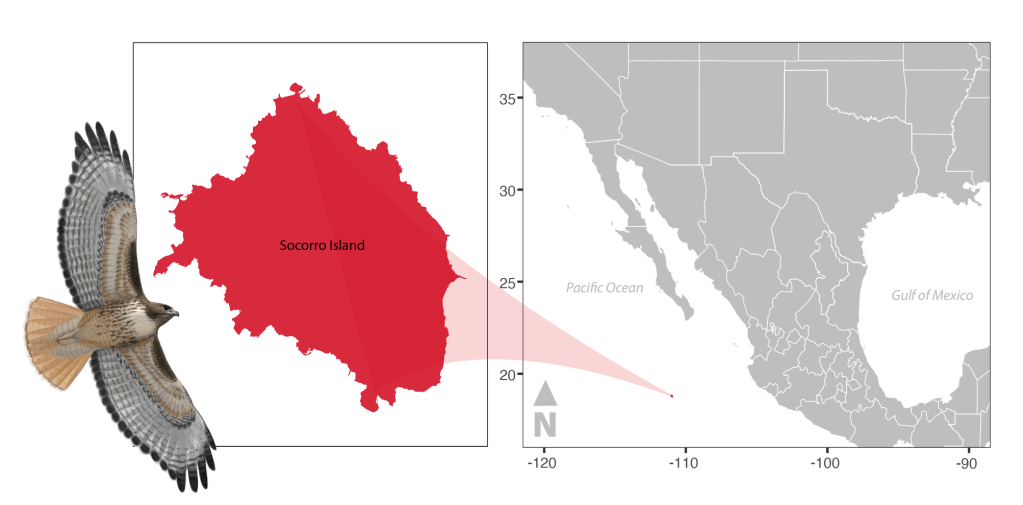

Restricted to Socorro Island, some 600 km west of Jalisco, Mexico, the Socorro Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis socorroensis) is a fascinating and poorly known taxon (Preston and Beane 2020). Despite its uniqueness, the ecology of this island endemic subspecies has been little studied, and its plumages and identification traits are likewise poorly understood. It has apparently adapted to feed on land crabs (Johngarthia oceanica), though its diet is reportedly quite varied (Wehtje et al. 1993, Rodriguez-Estrella et al. 1996), including preying on the critically endangered Townsend’s Shearwater (Puffinus auricularis). More study is needed to clarify its relationships in the broader Red-tailed Hawk complex.

Taxonomic Background

Buteo jamaicensis socorroensis Nelson 1898

Type Specimen. There are three syntypes (cotypes) in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History collection taken from Socorro in the late 1800s: USNM 50761, collected by A. J. Grayson, 24 April 1868 (specimen journal entry date) (Figs 2a-d); and a male and female collected by C. H. Townsend on 8 March 1889, USNM 117499 and 117500 (Appendix 1). Apparently these three specimens were used as the basis for the description ultimately provided by Ridgway for this taxon in Salvin et al. (1899).

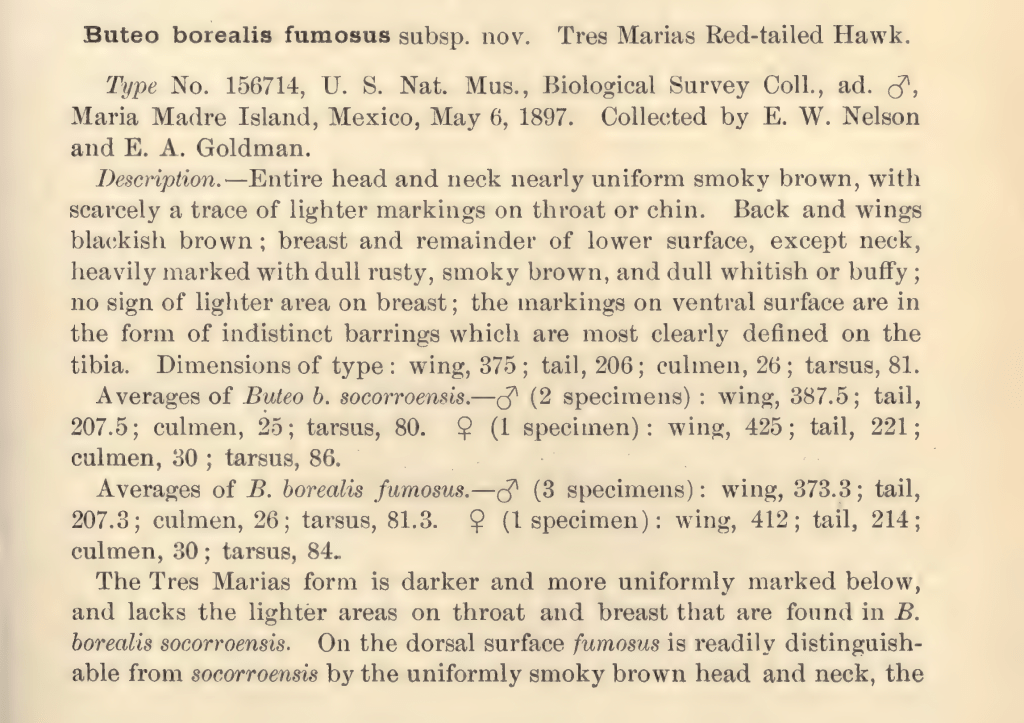

Taxonomic History. This taxon has a rather confusing history, and our interpretation of the historical literature follows that of Peters (1931) and Deignan (1961). Ridgway (1880) first named this taxon in his publication, but did not provide a type description or designate a type specimen; thus Ridgway’s 1880 name is a nomen nudum (naked name) (Fig 3). Apparently his inclusion of this taxon was based on the results of an expedition to Socorro by Grayson (1871), in which Grayson described a hawk occurring on Socorro Island and identified it as “Buteo borealis var. montanus” (Fig 4) and collected a specimen (Figs 2a-d) (montanus is a now defunct taxon that at the time was considered to refer to the ‘Western’ Red-tailed Hawk, but has been subsequently subsumed into the broader B. j. calurus complex). Presumably Ridgway (1880) recognized the significance of the Socorro Island form and decided to name it as a new subspecies: B. j. socorroensis, but since he provided no descriptive details, the taxon’s authorship fortuitously falls to Nelson (1898), who inadvertently provided a minimal description of B. j. socorrosensis in the process of describing a new taxon of Red-tailed Hawk from the Tres Marias Islands: B. j. fumosus (Fig 5). While Nelson’s description of socorroensis was basic, his details precede those provided by Ridgway in Salvin et al. (1899) a year later. Salvin et al. (1899) prompted Ridgway to provide a more complete description of socorroensis for their publication (Appendix 2). Presumably Ridgway used the three specimens from Socorro (Figs 2a-d, Appendix 1) as the basis for his description. Note: The Salvin and Godman manuscript for the Falconidae was in preparation when Salvin died, and it was continued and finished by Godman and Sharpe, thus we credit all three authors (Fig 6).

Identification

Identification material in the literature is lacking (e.g., not covered in guides to Mexico and Central America by Howell and Webb (1995), or by Clark and Schmitt (2017)). Historical literature focuses more on the life history aspects of this taxon rather than its appearance, which makes sense given its far removal from other mainland forms: essentially, if you’re on Socorro Island, you are seeing Socorro Red-tailed Hawks. There is likewise little photographic material available for review in eBird/Macaulay Library, likely because access to the island is difficult. We reviewed all photographic material available in the Macaulay Library (N = 19; accessed 19 March 2025). We combine these sources in the ID description below, which is extremely provisional. Since the original description, most authors have noted this taxon’s more robust legs and feet when compared with other Red-tailed Hawk taxa (Salvin et al., Friedmann 1950, ). Jehl and Parkes (1982) suggest that socorroensis cannot be separated from calurus on plumage characters alone, and instead the main difference is in its “more robust legs and feet. The diameter of its tarsi and toes is obviously greater, but this is not revealed by standard linear measurements; comparative measurements should be made on osteological material, which is not available for the island form.” Adult. Light morph similar to calurus or hadropus but combination of rufous-washed underparts with whiter breast unusual, as well as more complex belly band pattern, with mix of blotches and bars (Figs 7-9). Dark morph probably not distinguishable from those taxa on plumage alone, but appears to average more uniformly dark below, as in the rarer dark examples of calurus (Figs 1 and 10). We were not able to find photos of any individuals that match the rufous-morph of calurus, with a decidedly orange-rufous breast and vent, so it is unclear whether this morph occurs at all in socorroensis. Juvenile. Little material available for review. Presumably similar to calurus and hadropus. Eyes potentially darker amber versus lemon yellow in calurus/hadropus (Figs 11-12). More study needed.

Polymorphism

Polymorphic, occurring in both light and dark morphs. Interestingly, all three of the syntypes are light morphs, and historical ornithologists only described the light morph (Ridgway, Friedmann). Jehl and Parkes (1982) noted this discrepancy, and they reported up to 65-75% dark morph birds during their visits in 1978 and 1981; a ratio very different from mainland populations of Mexico or the southwestern United States. Has the ratio of dark morph to light morph changed over time on Socorro, or could the ornithologists of the 1800s have missed the dark morphs?

Range

Socorro Island (Isla Socorro), the largest of the four islands of the Revillagigedo Archipelago, lying approximately 600 km off the coast of western Mexico. A Red-tailed Hawk seen soaring above San Benedicto Island on 17 November 1953 was identified as “presumably” B. j. socorroensis in Brattstrom and Howell (1956), but no evidence was provided to support that identification. Given San Benedicto’s position roughly 50 km NNE of Socorro, it seems likely that the identification was made on the assumption that any Red-tailed Hawk on San Benedicto must have come from the neighboring island of Socorro. San Benedicto was denuded of vegetation and birdlife in 1952 when a new volcano erupted, causing the extinction of its endemic subspecies of Rock Wren (Salpinctes obsoletus exsul).

Movements

Presumably sedentary.

Status

Relatively common and broadly distributed on Socorro Island (Jehl and Parkes 1982). Estimates range from 15-25 pairs (Jehl and Parkes 1982, Wehtje et al. 1993) to 20-25 pairs (Rodriguez-Estrella et al. 1996). B. j. socorroensis has been identified as an extremely small but viable population that challenges longstanding concepts around minimum population size, and requires further study (Walter 1990). Walter (1990) notes: “Its persistence on this still rather undisturbed island raises pertinent questions about the validity of much-cherished concepts in conservation biology such as the impact of inbreeding, population fluctuations, variance in growth rates, and the effect of catastrophic perturbations.”

Discussion

Given the remote isolation of this taxon on a single offshore island, it begs further study. It seems highly unlikely that other subspecies of Red-tailed Hawks make it to Socorro with regularity, setting up a situation where this island form could evolve rapidly in isolation. Ornithologists of the past have noted aspects of its life history that seem quite different from other Red-tailed Hawk taxa (e.g., diet, ratio of dark/light morphs), but no focused research has been conducted on this taxon. Visitors to Socorro have focused more on the other endemic island avifauna, perhaps since the island form of Red-tailed Hawk is thus far recognized as a subspecies and not a distinct species. In addition to a focused life history study, a detailed genomic study is warranted. Only then will we know more about this intriguing island Red-tailed Hawk.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Guy M. Kirwan for help navigating the historical literature and helping clarify the taxonomic history.

References

Brattstrom, B.H., and T.R. Howell. 1956. The Bird of the Revilla Gigedo Islands, Mexico. Condor: Vol. 58 : Iss. 2 , Article 3.

Clark, W.S., and N.J. Schmitt. 2017. Raptors of Mexico and Central America. Princeton University Press.

Deignan, H.G. 1961. Type specimens of birds in the United States National Museum. Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

eBird. 2025. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Available: http://www.ebird.org. (Accessed: Date [March 19, 2025]).

Grayson, A.J. 1871. Exploring Expedition to the Island of Socorro, From Mazatlan, Mexico. Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History. Vol. XIV. 1870-1871 (page 301).

Howell, S.N.G, and S. Webb. 1995. A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. Oxford University Press.

Jehl, J.R., and K.C. Parkes. 1982. The status of the avifauna of the Revillagigedo Islands, Mexico. Wilson Bulletin 94:1 1-104.

Nelson, E.W. 1898. Descriptions of new birds from the Tres Marias Islands, western Mexico. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. Vol. XII: 5-11.

Peters, J.L. 1931. Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 1: page 232. Harvard University Press.

Preston, C.R., and R.D. Beane. 2020. Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.rethaw.01

Ridgway, R. 1880. A Catalogue of the Birds of North America. Proceedings of the United States National Museum. Volume III. 1880 (page 194).

Rodriguez-Estrella, R., J.L.L. de la Luz, A. Breceda, A. Castellanos, J. Cancino, and J. Llinas. 1996. Status, density and habitat relationships of the endemic terrestrial birds of Socorro Island, Revillagigedo Islands, Mexico. Biological Conservation 76: 195-202.

Salvin, O., F.D. Godman, and R.B. Sharpe. 1899. Biologia Centrali-Americana. Aves. Volume III. 1897-1904 (page 64).

Walter, H.S. 1990. Small Viable Population: The Red-Tailed Hawk of Socorro Island. Conservation Biology 4:4 441-443.

Wehtje, W., H.S. Walter, R. Rodriguez Estrella, J. Llinas, and A. Castellanus Vera. 1993. An annotated checklist of the birds of Isla Socorro, Mexico. Western Birds 24:1 1-16.

Appendix 1

B. j. socorroensis syntype specimens.

Adult male Socorro Red-tailed Hawk, syntype USNM 117499, collected 8 March 1889 by C. H. Townsend. Photos courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

Adult female Socorro Red-tailed Hawk, syntype USNM 117500, collected 8 March 1889 by C. H. Townsend. Photos courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.